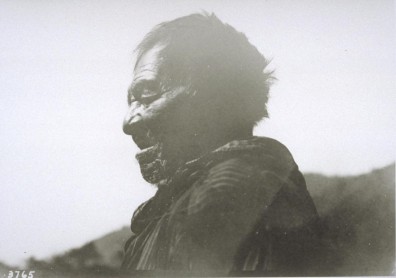

Im reading Kroebers Handbook Of The Indians Of California, which is both fascinating and gruesome. The Chimariko were a small tribe occupying a 20-mile stretch of the Trinity River in Northern California. In 1777, they numbered 1000; in 1851, they numbered 250; in 1910, the census placed their numbers at one toothless old woman and one crazy old man. He is pictured above.

They were an ancient tribe, having spent several thousand years (perhaps twelve thousand) fishing for salmon on the Trinity River; they may have been the oldest tribe in the area. Their language was a Hokan branch, similar in root to some of the other local tribes, including the Shasta and Karok; but was unique to the Chimariko, and barely preserved after the tribes extinction by John Peabody Harrington, who documented the basic structure by extensively interviewing the last speaker of Chimariko, Sally Noble, in the 1920s. She was presumably the toothless old woman referred to in the 1910 census; her mother was Chimariko, and her father was Tsungwe.

They were not a social tribe; they kept to themselves and were quite territorial. There are some references among the Hupa to the presence of Chimariko at their quite-popular dances, and some of the rituals of the Chimariko echoed those of other northwestern tribes; but generally, they were a people unto themselves.

The miners and trappers arrived in the 1840s. Their operations intruded into Chimariko territory; their mining methods left the Trinity River and Redwood Creek clouded with silt, and killed off the salmon. The Chimariko responded with violence in the 1860s in an attempt to repel the invaders, and were wiped out.

The US government at the time still paid cash for murdering Indians in the area. Out-of-work miners would routinely band together and attack Indian villages, burning them to the ground and slaughtering all inhabitants, for which they could then claim a bounty from the government. Several million dollars was paid out in this way; a considerable sum for the time.

Many tribes in the area suffered complete annihilation at the hands of the miners and the US Army. Most of their history is completely unknown. So many lives passing by, in hundreds of generations; so many stories, so much love and war and struggle, all lost, forever. I read the small section on the Chimariko, and then imagined myself as one for a moment.

Paradise on the Trinity, for thousands of years. Fishing, hunting, talking in the sweat lodge, dancing, raising children. Suddenly, contemptuous pale alien strangers arrive to strip the land of resources. Soon, everyone and everything youve ever known is dead, gone, and forever forgotten. Your ancestral lands and holy places are now parcels bought by retired corporate executives, with septic tanks and wine cellars, double garages and rustic fences. No one knows anything about you anymore. Your family has disappeared like a wisp of smoke.

What is that like?