Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumThe Weight of the World

Last edited Sun Oct 4, 2015, 11:05 AM - Edit history (1)

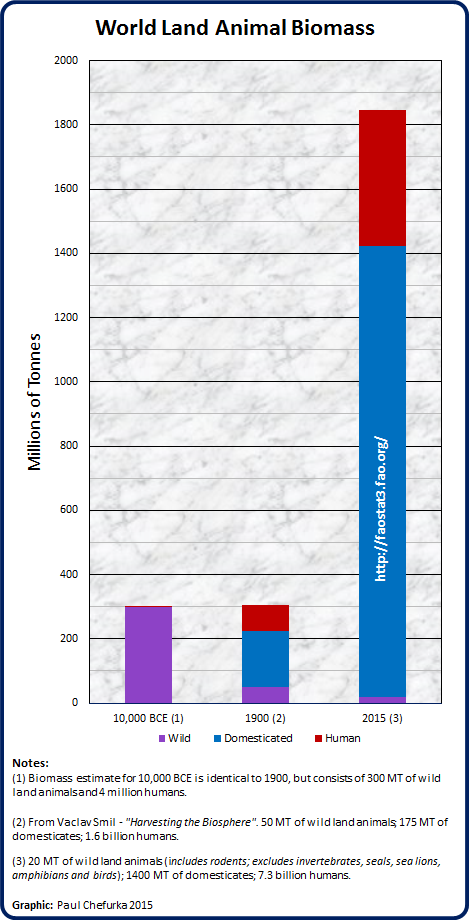

This article gives the background and explanation of what is, to my mind at least, the single most important piece of work I’ve done in the last decade. It is the graphical summary of what has happened to the the total weight of the world’s large land animals (my preferred technical term is “animal biomass”) over the last 12,000 years, from before the dawn of agriculture to the beginning of last week.

To kick things off, I will happily admit to being a graph geek. For me, graphs have a touch of scientific magic. They are a vehicle on which dry, raw numbers can slide into our brain through the open portal of its enormous visual processing capacity. Our visual cortex translates what we see, and feeds the results simultaneously into our intellectual processing circuits and our emotional limbic system.

A well-chosen graphic is therefore probably the best way to communicate the visceral significance of what I discovered as I probed three interconnected questions: How much of the world's biomass consists of land animals? How is that animal biomass apportioned between wild animals, domesticated animals and human beings? And how have this biomass and its proportions changed over the last 12,000 years?

The graph tells that enormous story with great economy, and does so with as much certainty as an amateur like me can achieve using publicly available information. I find its message and implications to be absolutely breathtaking.

The Graph:

[center] [/center]

[/center]

The Excel file containing all the data I used to make the graph are on Dropbox. Anyone may download it and use it freely. There are no usage or copyright restrictions on it. Here is the link:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/jtd0e3qokd0qk7p/AnimalBiomass.xlsx

Background

My interest in this topic was originally piqued by an xkcd cartoon that some of you may have seen. If you haven’t seen it, it’s at this link, along with a discussion: http://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/1338:_Land_Mammals

The information in that cartoon startled me (if that’s the right way to describe bug-eyed astonishment.) I decided to see if I could reproduce its findings on my own, and possibly refine them beyond the simple throwaway form of a cartoon.

The first thing I found when I began searching the net for information was a paper published in 2011 by the Canadian scientist Vaclav Smil. Fortunately Dr. Smil is about as authoritative and reliable a source on these sorts of topics as one could ask for. According to the short bio on his web site:

He has published 35 books and more than 400 papers on these topics. He is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of Manitoba, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (Science Academy), and the Member of the Order of Canada; in 2010 he was listed by Foreign Policy among the top 100 global thinkers.

He has worked as a consultant for many US, EU and international institutions, has been an invited speaker in nearly 400 conferences and workshops in the USA, Canada, Europe, Asia and Africa, and has lectured at many universities in North America, Europe and East Asia.

Dr. Smil’s paper is titled Harvesting the Biosphere. In it, he gives data for the weight of the world's wild and domesticated land animals for the years 1900 and 2000. These are very fortuitous dates for our purpose. The era of animal-powered farming was just ending in 1900 as fossil fuels began to revolutionize the world’s agriculture. By the year 2000 of course, the modern industrial food system was firmly in place.

The center column of the graph, its “anchor point”, is taken directly from the data in Table 2 of Dr. Smil's paper.

The Situation from 10,000 BCE to 1900 AD

Since I wanted to explore how animal life on the land surface of our planet, where we humans live, work and play, has changed from before the invention of agriculture until today, I needed an estimate for the situation in 10,000 BCE. That turned out to be easier said than done. I could find no authoritative estimates in the literature for the world’s animal biomass at that time, so I decided to create my own from first principles. The principle I started from was that of “carrying capacity”: the maximum amount of life an environment can support with only the basic natural inputs of sun, soil and water.

When you consider a land area as large as that of the entire Earth (~150 million square kilometers of land), over a long period when there is relatively little climate change or other outside disturbance, its carrying capacity measured in millions of tonnes of animal biomass will remain approximately constant. In our case, that means it was about the same in 10,000 BCE as it was 12,000 years later.

There was relatively little climate change over this period, and even by 1900 human agricultural practices had not yet begun to amplify the land’s carrying capacity through the added input of of fossil fuels. As a result, it is reasonable to assume that the carrying capacity in 10,000 BCE was about the same as it was in 1900. Of course, back then there were no domesticated animals and very few humans, so virtually all of the animal biomass consisted of wild animals.

Resting on this chain of logic, the first column of the graph shows the wild animal biomass in 10,000 BCE being the same as the total of wild and domesticated animals plus humans in the center column: the total was about 300 million tonnes (MT). I would expect this total value to have remained approximately constant from 10,000 BCE until around 1900, though its makeup would have gradually changed as human numbers and activity increased.

In 10,000 BCE those 300 million tonnes were almost entirely made up of wild animals, but by 1900 the biomass of wild animals had dropped to about 50 MT to make ecological room for the growing number of humans and their domesticated animals. The reduction happened because humans appropriated the habitat of wild animals for our own use, a process known in ecological science as “competitive exclusion”. In the process we hunted out many of those wild animal populations, resulting in a 12,000 year wave of extinctions that continues today.

The Situation Today

After 1900 fossil fuels began to change the face of agriculture, with major consequences for the expansion of the human population and our domesticated animals.

Today, late in 2015, there are approximately 7.3 billion people on the planet, with an estimated average weight of 58 kg each. The resulting human biomass of about 425 MT is one-third greater than the biomass of all the land animals that existed just 12,000 years ago. It is also over five times the human biomass in 1900.

But as enormous as that number is, it pales in comparison to the biomass of our domesticated animals.

In order to get a reliable estimate for the biomass of domestic animals, I consulted the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Their database contains the number of all domestic animals on Earth for each year since 1961, broken down by the type of animal. With those numbers in hand, I searched for the average weight of each animal type, and simply multiplied that by the number of each animal in the FAO database for 2013 - the latest year for which the FAO has reliable records. Oh yes, I also included an estimate for cats and dogs, which the FAO does not record.

The total biomass of domestic animals comes out to 1400 MT, which eight times greater than it was in 1900. It should come as no surprise that the majority of this enormous mass consists of cows. Almost 900 MT, or 63% of the total weight of all livestock on Earth is cattle. That is also more than twice the weight of all human beings alive today.

The last question I had to answer was the biomass of wild animals today. That was more problematic, because there is no organization like the FAO that counts wild animals. Besides, they are hard to count anyway because they’re all out in the wild. To arrive at an answer I took an indirect approach.

I started with a set of on-line lists of population estimates for wild animals, retrieved from Wikipedia. Then I searched the net for average weight estimates for each type of animal, and multiplied the population number by the average weight to get the total biomass for each animal. I was careful to include mice and rats as well as elephants and kangaroos.

When that exercise was complete, I had come up with a rough estimate of 11.5 MT of wild animals. Next I had to decide how accurate I thought this number was. It’s certain that some species were missed in the tables I consulted, but I have no way of knowing how many, or which ones. Also, the last thing I want is to create an opportunity for those of a “denialist” persuasion to accuse me of underestimating the number of wild animals just to make a point. So I made an arbitrary decision to raise the total by about 75% to 20 MT. The actual number is very likely to be somewhere between 12 and 20 MT.

My final estimate of 20 MT indicates that the total amount of animal wildlife on the planet has dropped by 60% or more over the last 115 years. This is consistent with the 2014 report by the World Wildlife Fund that the amount of wildlife has declined by half since 1970.

Implications

The implications of this graph are quite serious, to put it mildly.

It is clear that our use of fossil fueled machinery in farming has exploded the amount of livestock - and in consequence the number of people - to a degree unparalleled in the history of the Earth, and has done so in the blink of a geological eye. And of course all the fossil fuel that has gone into farming has released CO2 into the atmosphere (hello, climate change!), along with all the CO2 released as we broke new land for agricultural purposes.

Even more serious is the implication that if the world’s fossil fuel supplies were to falter even slightly (hello, Peak Oil!) then livestock and human populations could fall rapidly as a result.

But perhaps the most serious implication is the damage that has been done to the web of life itself. In just 12,000 years, we have reduced the wild animal biomass by close to 95%. In its place we have overrun the planet with enormous quantities of less than 20 species of domesticated animals - including ourselves. The loss of biodiversity that this radical shift represents should be causing the ecologically-minded to wake up at night in a cold sweat. We have no way of knowing when some species that is critical to our survival (hello, honeybees?) might succumb to the relentless pressure of human competition, and blink out of existence.

Stock market bubbles have nothing on this bubble of human and animal life we have created in the biosphere. We are now in an extremely precarious situation - any slight ecological hiccup could easily knock the pins out from under the whole gigantic, fragile edifice.

So what can we do about it? Obviously, three candidates are population control, going vegan and changing our farming practices. Each has its problems, and they are not small ones.

Population control is a political “third rail” issue, and politicians won’t go there until the situation is far more desperate than it is now. Veganism is going to be a very tough sell to 7.3 billion people, many of them in developing countries where the demand for meat is growing as a result of their increasing affluence. Changing our farming practices would improve the overall quality of our food supply and perhaps reduce its carbon intensity, but will do little or nothing to directly reduce the numbers of either people or livestock.

My other major concern is that we may be close to the peak of the bubble. We can’t say that for certain of course, but the longer any bubble continues to grow, the more likely it becomes that it will run into a disruption of one sort or another. Climate change, economic collapse, resource depletion, warfare and epidemics are at the top of my personal list of probabilities. With a bubble this large and complex, a small pin-prick might be enough to start a cascade of failures racing through the system. In my opinion such a disruption may be no more than 20 years away, and perhaps somewhat less.

While we still have some time, we each need to do what we can to secure our personal situations and our communities, and to encourage others to think about doing the same. And perhaps, if you are so inclined, a heartfelt prayer or two might not be such a bad idea.

Best wishes to all.

Paul Chefurka

daleanime

(17,796 posts)GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)A friend with good connections just sent me this email:

I found it oddly sad/ironic that the lead editor of the magazine that so exemplifies our wild planet was unaware of these statistics. This is a punch in the gut factoid vs issues like energy decline and ocean acidification that to non-scientists seem like abstractions

He also sent it to Smil and a professor in the Department of Energy Resources Engineering at Stanford. We'll see what comes back.

Duppers

(28,130 posts)Keep us posted.

Duppers

(28,130 posts)You're right about the graph. I'm sending it out.

But prayer, Paul? Really?

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)I'm not much into telling people what to do or not do as the curtain closes.

Duppers

(28,130 posts)Isn't religion a big factor in people turning their backs on scientific truth, such as climate science, to begin with?

Sorry. I just watched:

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)We are all driven by belief, whether we call it religion or not - and we all need to justify our beliefs, whatever they may be. Religion is a just convenient self-justification tool, and it has the added advantage of satisfying our evolved need tor in-group membership and identification. Religion isn't an monolithically negative force in human affairs, as the Quakers (and latterly, to some degree, the Pope himself) have demonstrated.

When I look for negative forces in human affairs, I'm strongly inclined to throw politics, science, engineering and economics into the basket right alongside Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Judaism, Unitarianism and the thousand-and-one forms of Christianity. All are belief-based social systems to some degree.

Science = "belief based social system"

![]()

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Like trying to tell a fish that its nose is wet...

Duppers

(28,130 posts)PhD physicists in my immediate household who'll disagree with that assertion of yours. So does Lawrence Krauss.

Circling the drain.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)The wave of emotion that rises in people when I say things like "science is a belief system" is the universal sign of a core belief being challenged.

My father is a biochemist with a very heavy PhD, my mother is a physicist. Neither of them would agree with me either. So what? I don't base my opinions on whether others agree with me or not.

RiverLover

(7,830 posts)http://www.democraticunderground.com/112791506

Its all very sad.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Although the point of that article is much the same as mine, the author seriously underestimated the mass of domesticated animals, and so the scale of the problem. It's twice as bad as he thinks. ![]()

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)For those who hope that human beings as a whole will come to their senses and begin undo the damage, here is something to consider.

Whether one stops at the level of human social institutions or continues on down to evolutionary psychology or even thermodynamics as I have tried to do, the answer is the same. The positive feedback loops of human growth have a built-in ratchet effect that keeps them from unwinding. Whether we call it a Progress Trap, a Vicious Circle Principle, Infrastructural Determinism, a survival instinct, thermodynamic dissipation or Manifest Destiny is immaterial. They all simply speak to different appearances of the same phenomenon: irreversibility. There is a good reason nature has made this ratchet so hard to defeat. Without it, we would not be here today - for better and/or worse.

muriel_volestrangler

(101,407 posts)He reckons 80 MT of carbon in cattle (and puts carbon as 45% of 45%, ie 20%, of body mass). So that would be 400 MT of cattle (strictly cattle and water buffalo, I think, since that what he talks about in the paragraph above his Table 2) (with the roughly 13% increase the FAO gives in cattle numbers from 2000 to 2013, that would work out at roughly 450 MT, ie half your figure). He also reckons a total for all domesticated animals of 120 MT C in the year 2000, or 600 MT total.

He used different weights for cattle in different areas (in 1900, and in 2000); did you?

I can't tell if his figure for domesticated animals included poultry. Did yours? If you used his figures as the basis for 1900 (and thus 10,000 BC), I think the same method ought to be used for the present day.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Here is the data I used for livestock, which also available in the spreadsheet. As you can see, I included poultry.

[pre]

Animal ........ Number ...... Kg. .... MT

--------------------------------------------

Cattle: .... 1,467,548,724 .. 600 ... 881

Pigs: ......... 977,274,246 .. 180 ... 176

Buffalo: ..... 193,821,181 .. 600 ... 116

Sheep: .... 1,162,875,535 ... 45 ..... 52

Chickens: 20,887,055,000 .... 2.25 . 47

Goats: ....... 975,803,263 ... 40 ..... 39

Horses: ....... 59,769,280 .. 450 ..... 27

Camels: ....... 26,989,193 . 600 ..... 16

Rabbits: ... 4,843,575,000 .... 3 ..... 15

Asses: ......... 43,528,756 .. 200 ...... 9

Turkeys: ..... 461,614,000 ... 13 ...... 6

Mules: .......... 10,251,330 .. 400 ..... 4

Geese: ........ 340,115,000 .... 5 ...... 2

Ducks: ...... 1,185,743,000 .... 1.25 . 1[/pre]

The total weight of livestock is 1391 MT, to which I added a further 10 MT of domestic dogs, and 2.4 MT of domestic cats. It's all in the spreadsheet.

I didn't do my own bottom-up inventory for 1900 because trustworthy data is very hard to find, so I accepted Smil's aggregate data. However, for 2015 I wanted to do my own inventory, both because I wanted up-to-date numbers whose provenance I knew, and to see how close they came to other estimates out there, including Smil's. As you noticed there is a difference.

However, accounting a total of 400 MT for cattle, as per Smil's estimate, would require an average mass of only 275 kg per animal. That doesn't seem at all reasonable given the weight ranges reported in Wikipedia. My weight for cows was taken from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cattle#Weight, and was chosen to represent an average across breeds. In fact, the Wikipedia entry says this: "according to some sources, the average weight of all cattle is 753 kg." In reducing my estimate to 600 kg I deliberately moved to the low side in order to take juvenile animals into account. I did the same with the average weights of all domestic animals.

muriel_volestrangler

(101,407 posts)The can be very different in other continents. The FAO reckons an average adult weight of 313kg for the Gir breed in India, for instance.

Since Smil produced the 1900 figures, using details of different breeds on different continents, and did the same for 2000 (while knowing they have grown in size, in general), it seems to me that a graph which is basically about comparing the 1900 figure to the present day (2000 and 2015 could produce a small difference) should be using the same methods where possible - which it is.

(The next reference in the Wikipedia article after the '753 kg' claim goes to the FAO here, which says "The mean cow weight at parturition was 232 kg and at weaning of calf, 235 kg" - for the Ethiopian Highlands, which bears no relation at all to Wikipedia's "the average weight of all cattle is 753 kg (1,660 lb). Finishing steers in the feedlot average about 640 kg (1,410 lb); cows about 725 kg (1,598 lb), and bulls about 1,090 kg (2,400 lb)"![]() .

.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)I'll stick with 600 kg unless someone can show me another average that has some reasonable basis. I don't see anything in the data you've highlighted that would cause me to change my mind just yet.