General Discussion

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region Forums3-14-16 Bread Yes, but Roses Too in 2:00

http://laborhistoryin2.podbean.com/e/march-14-2016-bread-yes-but-roses-too/

March 14, 2016

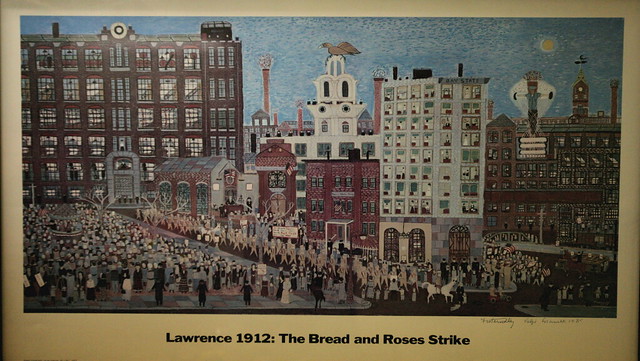

On this day in Labor History the year was 1912. That was the day that participants in the famed Bread and Roses strike, gathered in Lawrence, Massachusetts to celebrate their victory. The strike had begun in January and was a hard-fought battle.

2:00 minute audio at link.

juxtaposed

(2,778 posts)[url=https://flic.kr/p/33PMFy][img] [/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/33PMFy]The crowning jewel of the US labor movement."The Bread and Roses Strike" of 1912[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/juxtaposeesopatxuj/]juxtapose^esopatxuj[/url], on Flickr

[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/33PMFy]The crowning jewel of the US labor movement."The Bread and Roses Strike" of 1912[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/juxtaposeesopatxuj/]juxtapose^esopatxuj[/url], on Flickr

Bread and Roses: The 1912 Lawrence textile Strike

By Joyce Kornbluh

Early in January 1912 I.W.W. activities focused on a dramatic ten-week strike of 25,000 textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts. It became the most widely publicized I.W.W. conflict, acquainting the nation with the plight of the unskilled, foreign-born worker as well as with the organization's philosophy of radical unionism. "Lawrence was not an ordinary strike," wrote Brissenden in 1919, "It was a social revolution in parvo."

Lawrence in 1912 was a great textile center, outranking all others in the production of woolen and worsted goods. Its principal mills were those of the American Woolen Company, a consolidation of thirty-four factories in New England whose yearly output was valued at $45,000,000. The woolen and cotton mills employed over 40,000 persons, about half of Lawrence's population over age fourteen. Most of them were unskilled workers of many nationalities, who had come from Europe after 1900, attracted by the promises of labor Contractors representing the expanding textile industry in Massachusetts.

But despite a heavy, government tariff protection of the woolen industry, the wages and living standards of textile operatives had declined steadily since 1905. The introduction of the two-loom system in the woolen mills and a corresponding speed-up in the cotton industry had resulted in lay-offs, unemployment, and a drop in wages. A report of the U. S. Commissioner of Labor, Charles P. Neil, showed that for the week ending November 25, 1911, 22,000 textile employees, including foremen, supervisors, and office workers, averaged about $8.76 for a full week's work.

In addition, the cost of living was higher in Lawrence than elsewhere in New England. Rents, paid on a weekly basis, ranged from $1.00 to $6.00 a week for small tenement apartments in frame buildings which the Neil Report found "extra hazardous" in construction and potential firetraps. Congestion was worse in Lawrence than in any other city in New England; mill families in 58 percent of the homes visited by federal investigators found it necessary to take in boarders to raise enough money for rent.

Bread, molasses, and beans were the staple diet of most mill workers. "When we eat meat it seems like a holiday, especially for the children," testified one weaver before the March 1912 congressional investigation of the Lawrence strike.

Of the 22,000 textile workers investigated by Labor Commissioner Neil, well over half were women and children who found it financially imperative to work in the mills. Half of all the workers in the four Lawrence mills of the American Woolen Company were girls between ages fourteen and eighteen. Dr. Elizabeth Shapleigh, a Lawrence physician, wrote: "A considerable number of the boys and girls die within the first two or three years after beginning work . . . thirty-six out of every 100 of all the men and women who work in the mill die before or by the time they are twenty-five years of age. Because of malnutrition, work strain, and occupational diseases, the average mill worker's life in Lawrence was over twenty-two years shorter than that of the manufacturer, stated Dr. Shapleigh.

Responding in a small way to public pressure over the working conditions of textile employees, the Massachusetts state legislature passed a law, effective January 1, 1912, which reduced the weekly hours from fifty-six to fifty-four for working women and children. Workers feared that this would mean a corresponding wage cut, and their suspicions were sharpened when the mill corporations speeded up the machines and posted notices that, following January 1, the fifty-four-hour work week would be maximum for both men and women operatives.

The I.W.W. had been organizing among the foreign born in Lawrence since 1907 and claimed over a thousand members, but it had only about 300 paid up members on its rolls. About 2500 English-speaking skilled workers were organized by craft into three local unions of the A.F.L.'s United Textile Workers, but only about 208 of these were in good standing in 1912. The small, English-speaking branch of the I.W.W. sent a letter to President Wood of the American Woolen Company asking how wages would be affected under the new law. There was no reply. Resenment grew as the textile workers realized that a reduction of two-hours pay from their marginal incomes would mean, as I.W.W. publicity pointed out, three loaves of bread less each week from their meager diet.

Polish women weavers in the Everett Cotton Mills were the first to notice a shortage of thirty two cents in their pay envelopes on January 11. They stopped their looms and left the mill, shouting "short pay, short pay!" Other such outbursts took place throughout Lawrence. The next morning workers at the Washington and Wood mills joined the walkout. For the first time in the city's history, the bells of the Lawrence city ball rang the general riot alarm.