Science

Related: About this forumEaster Island and the Immune System.

For the last several months, I've been focusing, for professional reasons, my attention on the workings of the immune system, a subject I've mainly understood (at a low level) mostly by osmosis.

Today I was focusing on a particular biochemical aspect of it that relates to Alzheimer's disease, a cascade of biochemical triggers involved with macrophages and the response to "DAMP" and "PAMP," "Damage Associated Molecular Patterns" (wounds and lesions mostly) and "Pathogen Associated Molecular Patterns" respectively.

As a result, I stumbled upon this paper: Twenty-five years of mTOR: Uncovering the link from nutrients to growth (David M. Sabatini, PNAS October 25, 2017 114 (45) 11818-11825)

Rapamycin is a fairly well known component of many formulated systems where it works as an immunosuppressant agent; as the drug "sirolimus" (Rapamune) it is given to address a number of autoimmune diseases, immunogenic responses to biotherapeutics, to prevent rejection of implants - for instance cardiac stents are often coated with it - and transplants. I've seen it around quite a bit in my career, without ever thinking much about it or its origins.

Dr. Sabatini's paper (it's open sourced, anyone can read it), a retrospective on his career working on the mTOR receptor, on which rapamycin acts, informed me of this piece of it's history about which I did not know. My excerpt begins with a paragraph about discussion Dr. Sabatini had with his research adviser. I shared with my son as he enters a Ph.D program, a bit about "intellectual freedom:"

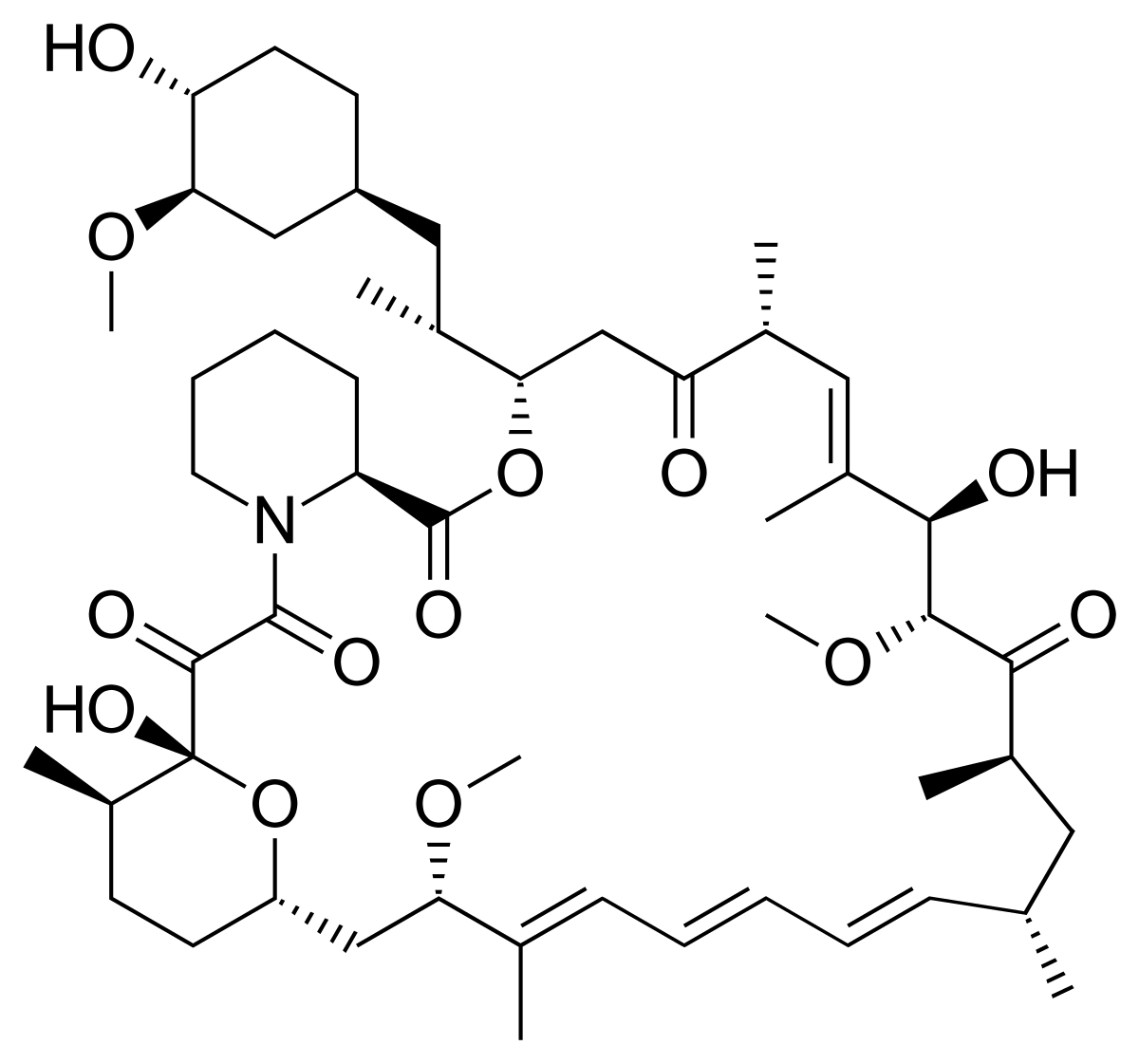

At that time, others in the laboratory were studying the effects of the immunosuppressant FK506 on neurons and using a structurally related molecule, rapamycin, as a negative control. We were fortunate to have rapamycin because, back then, it was not commercially available, and Sol had obtained it from Suren N. Sehgal at Wyeth-Ayerst (Fig. 2A). Sehgal—widely considered the father of rapamycin and its unrelenting champion until his death in 2003—had purified the compound in 1975 from bacteria found in soil collected on Easter Island (3). Sehgal had very kindly sent us a large amount, but just as importantly, he had also sent a book titled “Rapamycin Bibliography” with a little note wishing us luck. That book became my inspiration. It consisted mostly of abstracts describing the remarkable antifungal, immunosuppressive, and anticancer effects of rapamycin. It was clear that rapamycin inhibited the proliferation of a wide variety of cells ranging from lymphocytes and cancer cells to various species of yeast and preferentially delayed the G1 phase of the cell cycle (3–5). I had just finished the first 2 y of medical school and had learned how the immunosuppressant cyclosporin A was revolutionizing organ transplantation. At that point, I still thought I was going to be a practicing physician, so the medical applications of rapamycin were exciting to me and inspired me to determine how rapamycin works.

The bold and italics were added by me.

There's more to Easter Island than those big block heads.

I had no idea that a drug this important had been found is such an exotic place.

I have no particular religion but I was raised in one, and for various reasons which remain personal I celebrate Good Friday, but if you're a Christian or a secular bunny worshiper, I wish you a happy Easter.

Because of Easter Island's soil, a number of people who otherwise might have been dead, while not resurrected exactly, lived beyond their years.

in2herbs

(2,947 posts)mention bribes) could accelerate medical discoveries/cures if spent on that instead.

Very interesting post. I will read the paper. I won't necessarily understand it, but I'll read it. Thanks.

eppur_se_muova

(36,289 posts)Amazing how extensive has been the decades-long screening effort to find new antibiotics and the like from soil samples scattered across the globe. While you might collect a sample in one spot and miss something else just a few feet away, there's powerful motivation to acquire samples from every location that hasn't been previously examined. (Also worth remembering -- the first antibiotic known, penicillin, blew through a London window unbidden!)

NNadir

(33,544 posts)Rapamycin is a synthetically challenging molecule to be sure.

I'm sure someone's done a total synthesis, but it's nice that there's a bug that makes it for us.

eppur_se_muova

(36,289 posts)Some polyene, some polyketide, maybe an oxidized amino acid, and even a hydrogenated lignol(??). Maybe the only critical features of macrolide antibiotics are all those polar groups pointing inward, and a certain balance of conformational rigidity and flexibility that holds it open like a noose when not complexed to a cation. But that's getting outside my bailiwick, to be sure.

Natural selection works in mysterious ways. ![]()

NNadir

(33,544 posts)...from a lipopolysaccharide, which is very interesting, because LPS is a stimulant of the PBMC's that drive the innate immune system. People throw it into blood cell cultures all the time.

I've been dragged kicking and screaming into issues in cell based analysis. I will admit that learning about the complexity of the immune system and how its dysregulation leads to so many very serious diseases - I believe we can add Alzheimer's to the list - has been fascinating, and for me, as an old fat guy, a little scary.

I never thought that at my age I'd find myself embedded in an entirely new topic about which I knew next to nothing. Life is fun, then you die.