Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

General Discussion

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region ForumsHappy 151th anniversary, the (not really) transcontinental railroad

It wasn't really a transcontinental railroad, as there was still a river to cross in Sacramento to complete an all-rail route to the Pacific. Also, there was no bridge across the Missouri River between Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha, Nebraska. But never mind that.

Fri May 10, 2019: Happy 150th anniversary, the (not really) transcontinental railroad

UTAH | HOME

Cheers greet trains as thousands gather to mark 150th anniversary of transcontinental railroad

By Amy Joi O'Donoghue | @amyjoi16 | May 10, 2019, 3:12pm MDT

PROMONTORY SUMMIT, Box Elder — Thousands of people are making their way to Golden Spike National Historical Park Friday morning to mark the 150th anniversary of the driving of the golden spike that marked the completion of the transcontinental railroad.

The celebration begins with a ceremony that tells the story of the building of the first transcontinental railroad and recognizes the thousands of workers whose efforts made the railroad a reality.

The official ceremony begins just before 11 a.m. Tickets for the park are sold out for Friday and Saturday.

....

Cheers greet trains as thousands gather to mark 150th anniversary of transcontinental railroad

By Amy Joi O'Donoghue | @amyjoi16 | May 10, 2019, 3:12pm MDT

PROMONTORY SUMMIT, Box Elder — Thousands of people are making their way to Golden Spike National Historical Park Friday morning to mark the 150th anniversary of the driving of the golden spike that marked the completion of the transcontinental railroad.

The celebration begins with a ceremony that tells the story of the building of the first transcontinental railroad and recognizes the thousands of workers whose efforts made the railroad a reality.

The official ceremony begins just before 11 a.m. Tickets for the park are sold out for Friday and Saturday.

....

Editorial: 150 years ago, the nation united by a golden spike

May 10, 2019

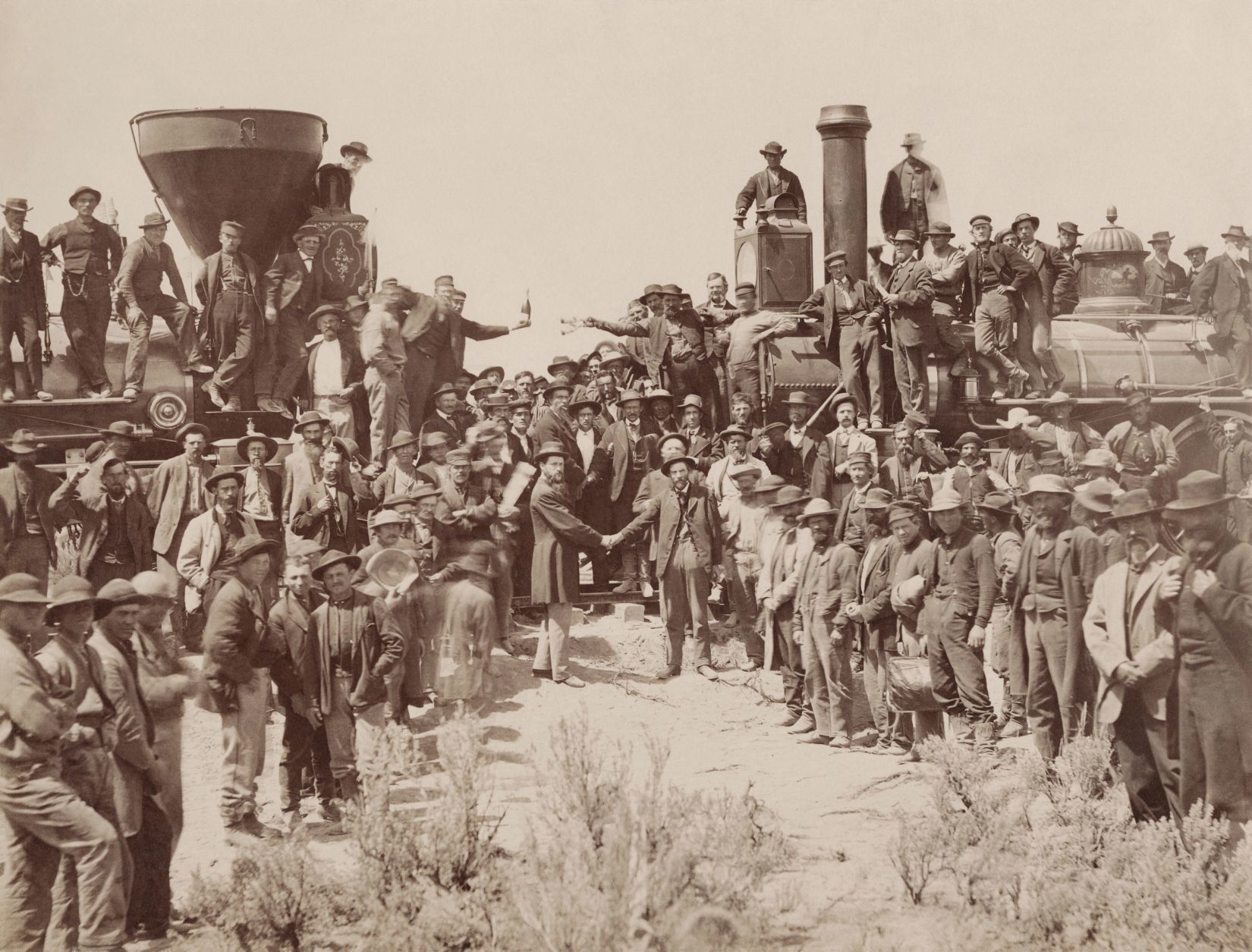

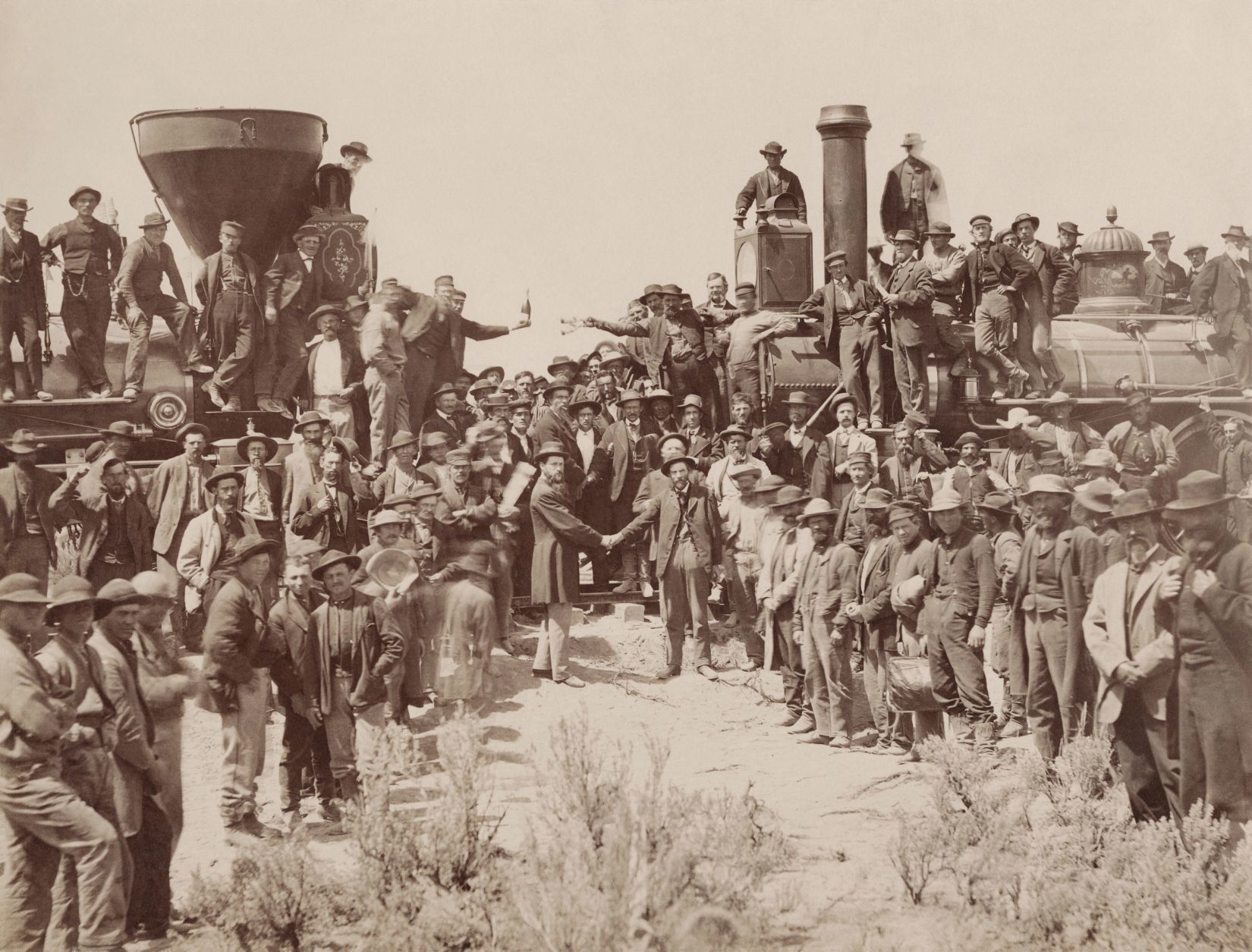

The ceremony to celebrate the driving of “the golden spike,” the last link in North America’s first transcontinental railroad, which took place 150 years ago today — May 10, 1869 at Promontory Point, Utah. The two men shaking hands in the center are Samuel S. Montague, Central Pacific Railroad (center left) and Grenville M. Dodge of the Union Pacific Railroad (center right). Notice the liquor bottles that the men hanging from the front of the locomotives are showing off. Those bottles were later removed from some photos, in deference to the temperance movement. Our editorial at left looks at the significance of the event — the railroad, not the airbrushing of the liquor bottles.

Courtesy of Yale University libraries

They huddled in telegraph offices across the country, from small towns all the way up to government offices in Washington. For 27 long minutes, the whole nation seemed to fall silent. Telegraph operators were told to stand down from sending any traffic so as to keep the lines clear as everyone waited for that one special sound.

One hundred and fifty years ago today, the United States witnessed what might qualify as its first mass media event. In the century and a half to come, Americans would gather around their televisions to watch a man step onto the moon, or any number of televised spectaculars and horrors. But on the afternoon of May 10, 1869, they gathered in telegraph offices listening for a series of clicks that said nothing but also said everything.

More than half a continent away, on a remote stretch of Utah desert, an event that would transform the nation was taking place. From the west came a locomotive from the Union Pacific; from the east came one from the Central Pacific. There they sat, nearly cow-catcher to cow-catcher. Between them lay the last gap of what would soon become North America’s first transcontinental railroad. The pounding of the ceremonial “golden spike” would unite the nation, both symbolically and literally. As with many things, this was a story driven by politics, graft and, in the end, some theatrics and maybe even a little of what today we’d call “fake news.”

Being Virginians, we must start with Thomas Jefferson. His Louisiana Purchase didn’t extend all the way to the West Coast but Meriwether Lewis and William Clark went there anyway. The precise status of the Pacific Northwest remained in dispute for several decades, claimed by both the U.S. and Great Britain. Jefferson, though, was skeptical that it would wind up with either. He thought the Northwest would become “a great, free, and independent empire on that side of our continent.”

That didn’t happen, but the Mexican War did. Suddenly the United States owned a big swath of the West Coast. That was 1848. Just a week before American ownership of California became official, gold was discovered. The gold rush was on — along with a political debate about how to create a transportation network to unite a nation that spanned an entire continent. In practical terms, that meant a railroad but in even more practical terms, the question was where? In those pre-Civil War days, the North wanted a northern route. The South wanted a southern route. Nothing much got done. Then came the Civil War.

You might think that the war would have complicated things. Actually, the war simplified them. There were no longer any Southerners in Congress to object to a non-southern route. The Civil War Congress was also run by Republicans. That new political party had been formed primarily as an anti-slavery party, but it was also the national infrastructure party. One of its lesser-known planks had been to endorse a transcontinental railroad. In 1862, President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act, which set in motion the entire enterprise. The act also settled on a route safely away from pesky Southerners.

....

May 10, 2019

The ceremony to celebrate the driving of “the golden spike,” the last link in North America’s first transcontinental railroad, which took place 150 years ago today — May 10, 1869 at Promontory Point, Utah. The two men shaking hands in the center are Samuel S. Montague, Central Pacific Railroad (center left) and Grenville M. Dodge of the Union Pacific Railroad (center right). Notice the liquor bottles that the men hanging from the front of the locomotives are showing off. Those bottles were later removed from some photos, in deference to the temperance movement. Our editorial at left looks at the significance of the event — the railroad, not the airbrushing of the liquor bottles.

Courtesy of Yale University libraries

They huddled in telegraph offices across the country, from small towns all the way up to government offices in Washington. For 27 long minutes, the whole nation seemed to fall silent. Telegraph operators were told to stand down from sending any traffic so as to keep the lines clear as everyone waited for that one special sound.

One hundred and fifty years ago today, the United States witnessed what might qualify as its first mass media event. In the century and a half to come, Americans would gather around their televisions to watch a man step onto the moon, or any number of televised spectaculars and horrors. But on the afternoon of May 10, 1869, they gathered in telegraph offices listening for a series of clicks that said nothing but also said everything.

More than half a continent away, on a remote stretch of Utah desert, an event that would transform the nation was taking place. From the west came a locomotive from the Union Pacific; from the east came one from the Central Pacific. There they sat, nearly cow-catcher to cow-catcher. Between them lay the last gap of what would soon become North America’s first transcontinental railroad. The pounding of the ceremonial “golden spike” would unite the nation, both symbolically and literally. As with many things, this was a story driven by politics, graft and, in the end, some theatrics and maybe even a little of what today we’d call “fake news.”

Being Virginians, we must start with Thomas Jefferson. His Louisiana Purchase didn’t extend all the way to the West Coast but Meriwether Lewis and William Clark went there anyway. The precise status of the Pacific Northwest remained in dispute for several decades, claimed by both the U.S. and Great Britain. Jefferson, though, was skeptical that it would wind up with either. He thought the Northwest would become “a great, free, and independent empire on that side of our continent.”

That didn’t happen, but the Mexican War did. Suddenly the United States owned a big swath of the West Coast. That was 1848. Just a week before American ownership of California became official, gold was discovered. The gold rush was on — along with a political debate about how to create a transportation network to unite a nation that spanned an entire continent. In practical terms, that meant a railroad but in even more practical terms, the question was where? In those pre-Civil War days, the North wanted a northern route. The South wanted a southern route. Nothing much got done. Then came the Civil War.

You might think that the war would have complicated things. Actually, the war simplified them. There were no longer any Southerners in Congress to object to a non-southern route. The Civil War Congress was also run by Republicans. That new political party had been formed primarily as an anti-slavery party, but it was also the national infrastructure party. One of its lesser-known planks had been to endorse a transcontinental railroad. In 1862, President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act, which set in motion the entire enterprise. The act also settled on a route safely away from pesky Southerners.

....

The lines met at Promontory Summit, not Promontory Point. Also, the Central Pacific came into Promontory Summit from the west and the Union Pacific from the east. They did quickly alter the original title, which said that 2019 was the 100th anniversary of the event. Details.

Thu May 10, 2018: Happy 149th anniversary, railroad from Omaha to Sacramento, but not the Atlantic to the Pacific

Previously at DU:

Tue May 10, 2016: Happy 147th Birthday, Transcontinental Railroad.

Fri May 10, 2013: Happy 144th Birthday, Transcontinental Railroad!!!

Related:

Sat Mar 12, 2016: At the Throttle: Does anybody really know what time it is?

At the ceremony for the driving of the "Last Spike" at Promontory Summit, Utah, May 10, 1869. Andrew J. Russell (1830-1902), photographer

A.J. Russell image of the celebration following the driving of the "Last Spike" at Promontory Summit, U.T., May 10, 1869. Because of temperance feelings the liquor bottles held in the center of the picture were removed from some later prints.

First Transcontinental Railroad

The First Transcontinental Railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the "Overland Route" ) was a 1,907-mile (3,069 km) contiguous railroad line constructed in the United States between 1863 and 1869 west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers to connect the Pacific coast at San Francisco Bay with the existing eastern U.S. rail network at Council Bluffs, Iowa. The rail line was built by three private companies largely financed by government bonds and huge land grants: the original Western Pacific Railroad Company between Oakland and Sacramento, California (132 mi or 212 km), the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California eastward from Sacramento to Promontory Summit, Utah Territory (U.T.) (690 mi or 1,110 km), and the Union Pacific westward to Promontory Summit from the road's statutory Eastern terminus at Council Bluffs on the eastern shore of the Missouri River opposite Omaha, Nebraska (1,085 mi or 1,746 km).

Opened for through traffic on May 10, 1869, with the ceremonial driving of the "Last Spike" (later often called the "Golden Spike" ) with a silver hammer at Promontory Summit,[4][5] the road established a mechanized transcontinental transportation network that revolutionized the settlement and economy of the American West by bringing these western states and territories firmly and profitably into the "Union" and making goods and transportation much quicker, cheaper, and more flexible from coast to coast.

The First Transcontinental Railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the "Overland Route" ) was a 1,907-mile (3,069 km) contiguous railroad line constructed in the United States between 1863 and 1869 west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers to connect the Pacific coast at San Francisco Bay with the existing eastern U.S. rail network at Council Bluffs, Iowa. The rail line was built by three private companies largely financed by government bonds and huge land grants: the original Western Pacific Railroad Company between Oakland and Sacramento, California (132 mi or 212 km), the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California eastward from Sacramento to Promontory Summit, Utah Territory (U.T.) (690 mi or 1,110 km), and the Union Pacific westward to Promontory Summit from the road's statutory Eastern terminus at Council Bluffs on the eastern shore of the Missouri River opposite Omaha, Nebraska (1,085 mi or 1,746 km).

Opened for through traffic on May 10, 1869, with the ceremonial driving of the "Last Spike" (later often called the "Golden Spike" ) with a silver hammer at Promontory Summit,[4][5] the road established a mechanized transcontinental transportation network that revolutionized the settlement and economy of the American West by bringing these western states and territories firmly and profitably into the "Union" and making goods and transportation much quicker, cheaper, and more flexible from coast to coast.

A week later, they began service.

Display ads for the CPRR and UPRR the week the rails were joined on May 10, 1869

There was no bridge across the Missouri River until 1873:

Union Pacific route

The Union Pacific's 1,087 miles (1,749 km) of track started at MP 0.0 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, on the eastern side of the Missouri River. This was chosen by the President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, as the location of its Transfer Depot where up to seven railroads could transfer mail and other goods to Union Pacific trains bound for the west. Initially trains crossed the river by ferry to get to the western tracks starting in Omaha, Nebraska, in the newly formed Nebraska Territory. Winter and spring caused severe problems as the Missouri River froze over in the winter; but not well enough to support a railroad track plus train. The train ferries had to be replaced by sleighs each winter. Getting freight across a river that flooded every spring and filled with floating debris and/or ice floes became very problematic for several months of the year. (Starting in 1873, the railroad traffic crossed the river over the new 2,750 feet (840 m) long, eleven span, truss Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge to Omaha, Nebraska.)

The Union Pacific's 1,087 miles (1,749 km) of track started at MP 0.0 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, on the eastern side of the Missouri River. This was chosen by the President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, as the location of its Transfer Depot where up to seven railroads could transfer mail and other goods to Union Pacific trains bound for the west. Initially trains crossed the river by ferry to get to the western tracks starting in Omaha, Nebraska, in the newly formed Nebraska Territory. Winter and spring caused severe problems as the Missouri River froze over in the winter; but not well enough to support a railroad track plus train. The train ferries had to be replaced by sleighs each winter. Getting freight across a river that flooded every spring and filled with floating debris and/or ice floes became very problematic for several months of the year. (Starting in 1873, the railroad traffic crossed the river over the new 2,750 feet (840 m) long, eleven span, truss Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge to Omaha, Nebraska.)

The western end did not reach the Pacific Ocean at first either:

Aftermath

Railroad developments

When the last spike was driven, the rail network was not yet connected to the Atlantic or Pacific but merely connected Omaha to Sacramento. To get from Sacramento to the Pacific, the Central Pacific purchased the struggling Western Pacific Railroad (unrelated to the railroad of the same name that would later parallel its route) and resumed construction on it, which had halted in 1866 due to funding troubles. In November 1869, the Central Pacific finally connected Sacramento to the east side of San Francisco Bay by rail at Oakland, California, where freight and passengers completed their transcontinental link to the city by ferry.

Railroad developments

When the last spike was driven, the rail network was not yet connected to the Atlantic or Pacific but merely connected Omaha to Sacramento. To get from Sacramento to the Pacific, the Central Pacific purchased the struggling Western Pacific Railroad (unrelated to the railroad of the same name that would later parallel its route) and resumed construction on it, which had halted in 1866 due to funding troubles. In November 1869, the Central Pacific finally connected Sacramento to the east side of San Francisco Bay by rail at Oakland, California, where freight and passengers completed their transcontinental link to the city by ferry.

Wikipedia: Golden spike

Eighty years later, this is the terrain that was crossed:

{The link went bad over a year ago. I'll find another one that works.}

Cue the inevitable posts about imperialism and genocide in 5 ... 4 ... 3 ....

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

3 replies, 756 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (3)

ReplyReply to this post

3 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

Happy 151th anniversary, the (not really) transcontinental railroad (Original Post)

mahatmakanejeeves

May 2020

OP

The first railroad bridge across the Mississipi River was completed in 1856.

mahatmakanejeeves

May 2020

#3

flotsam

(3,268 posts)1. Fake News!

I don't see Cullen Bohanon in any of the photographs!!!

Wounded Bear

(58,645 posts)2. I don't believe they had bridged the Mississippi yet, either...

mahatmakanejeeves

(57,393 posts)3. The first railroad bridge across the Mississipi River was completed in 1856.

I didn't know. I had to look it up. That's earlier than I would have guessed.

Bridging the Mississippi

The Railroads and Steamboats Clash at the Rock Island Bridge

Summer 2004, Vol. 36, No. 2

By David A. Pfeiffer

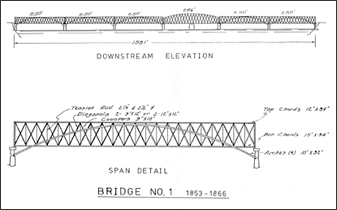

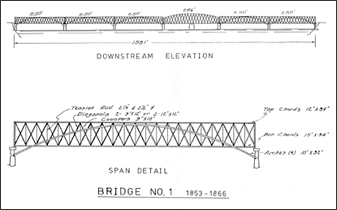

Downstream elevation drawing of the first bridge at Rock Island. (William Riebe, "The Government Bridge," The Rock Island Digest)

On April 22, 1856, the citizens of Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa, cheered as they watched three steam locomotives pull eight passenger cars safely across the newly completed Chicago and Rock Island railroad bridge over the Mississippi River. The first railroad bridge across the Mississippi was open for business. Now the people of eastern Iowa could reach New York City by rail in no more than forty-two hours.

The construction and completion of this bridge came to symbolize the larger issues affecting transcontinental commerce and sectional interests. Backers of a railroad across the country were divided between those who favored a northern route and those who advocated a southern one. The bridge also pitted steamboats against the railroads, and these disagreements were decided in the federal courts.

Two notable players in the controversy surrounding the bridge were men who would later face each other on a grander stage: Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. Lincoln was the attorney for the bridge company in litigation brought by the steamship interests. Davis, as secretary of war, took an active role in the contest between northern and southern routes for a transcontinental railroad.

The Rock Island Bridge was built for the purpose of uniting the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad, which had just reached Rock Island from Chicago in 1854, and the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad in Iowa, which was building from Davenport toward Council Bluffs on the western end of the state during 1853. Proponents of the project touted Rock Island as an ideal location for the bridge as it provided a direct rail link between the city and state of New York, the Mississippi Valley, and the Far West. Project engineers, drawing on an 1837 topographical survey by Lt. Robert E. Lee and other surveys, deemed the site ideal.

Because the boundary between Illinois and Iowa was in the center of the main channel of the Mississippi River and both railroad's charters differed on their legal origin and terminal points, special legislation and a new charter was necessary to unite the two railroads. The problem was solved by an act of the Illinois legislature in 1853 incorporating the Railroad Bridge Company with the power to "build, maintain, and use a railroad bridge over the Mississippi River . . . in such a manner as shall not materially obstruct or interfere with the free navigation of said river." This condition would become a crucial point in future litigation.

The construction of the bridge started on July 16, 1853, and lasted for three years. The construction involved three sections—a bridge across a narrow portion of the river between the Illinois shore and the island, a line of tracks across Rock Island, and the long bridge between the island and the Iowa shore.

{snip}

The fight, however, was not over. On the morning of April 21, 1856, the bridge was completed, and the first trains rolled across it. Again, speeches were made and bands played. The Father of Waters had been crossed. Then disaster struck.

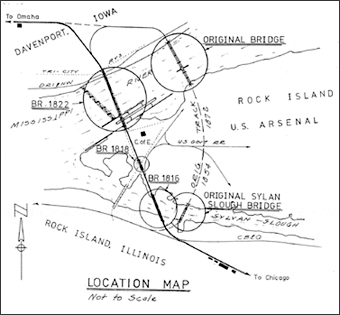

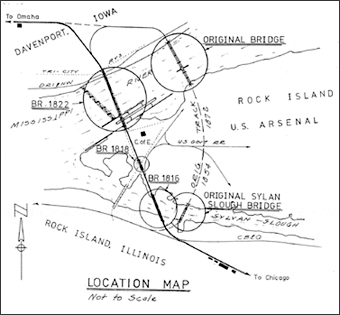

This drawing shows the locations of the various Rock Island bridges over the years. (William Riebe, "The Government Bridge," The Rock Island Digest)

A Collision Brings the Bridge to Court

Just fifteen days after the celebration of the completion of the bridge, part of the bridge was wrecked and burned as a result of a steamboat collision. This incident set the stage for act two of the court battle that helped to settle the issue of whether railroads could cross navigable streams. This incident also brought into the public eye an Illinois attorney by the name of Abraham Lincoln.

The story goes like this. As darkness fell on the evening of May 6, the steamer Effie Afton moved slowly upriver toward the newly completed bridge. The vessel blew her whistle signaling that she was moving through the draw. The draw slowly opened and the steamboat moved through. Some two hundred feet after the Effie Afton cleared the draw, she heeled hard to the right. Her starboard engine stopped, the port power seemingly increased. She struck the span next to the opened draw. The impact caused a great deal of damage to both the bridge and the boat. Then a stove in one of the cabins was knocked over and its fire spread rapidly to the deck and then to the bridge timbers. The vessel burned to cinders within five minutes. One span was completely destroyed, and there was some pier damage as well as minor damage to the rest of the bridge. By the following day, the rest of the bridge caught fire and was completely destroyed. Steamboats up and down the river celebrated, blowing whistles and ringing bells.

{snip}

The Railroads and Steamboats Clash at the Rock Island Bridge

Summer 2004, Vol. 36, No. 2

By David A. Pfeiffer

Downstream elevation drawing of the first bridge at Rock Island. (William Riebe, "The Government Bridge," The Rock Island Digest)

On April 22, 1856, the citizens of Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa, cheered as they watched three steam locomotives pull eight passenger cars safely across the newly completed Chicago and Rock Island railroad bridge over the Mississippi River. The first railroad bridge across the Mississippi was open for business. Now the people of eastern Iowa could reach New York City by rail in no more than forty-two hours.

The construction and completion of this bridge came to symbolize the larger issues affecting transcontinental commerce and sectional interests. Backers of a railroad across the country were divided between those who favored a northern route and those who advocated a southern one. The bridge also pitted steamboats against the railroads, and these disagreements were decided in the federal courts.

Two notable players in the controversy surrounding the bridge were men who would later face each other on a grander stage: Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. Lincoln was the attorney for the bridge company in litigation brought by the steamship interests. Davis, as secretary of war, took an active role in the contest between northern and southern routes for a transcontinental railroad.

The Rock Island Bridge was built for the purpose of uniting the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad, which had just reached Rock Island from Chicago in 1854, and the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad in Iowa, which was building from Davenport toward Council Bluffs on the western end of the state during 1853. Proponents of the project touted Rock Island as an ideal location for the bridge as it provided a direct rail link between the city and state of New York, the Mississippi Valley, and the Far West. Project engineers, drawing on an 1837 topographical survey by Lt. Robert E. Lee and other surveys, deemed the site ideal.

Because the boundary between Illinois and Iowa was in the center of the main channel of the Mississippi River and both railroad's charters differed on their legal origin and terminal points, special legislation and a new charter was necessary to unite the two railroads. The problem was solved by an act of the Illinois legislature in 1853 incorporating the Railroad Bridge Company with the power to "build, maintain, and use a railroad bridge over the Mississippi River . . . in such a manner as shall not materially obstruct or interfere with the free navigation of said river." This condition would become a crucial point in future litigation.

The construction of the bridge started on July 16, 1853, and lasted for three years. The construction involved three sections—a bridge across a narrow portion of the river between the Illinois shore and the island, a line of tracks across Rock Island, and the long bridge between the island and the Iowa shore.

{snip}

The fight, however, was not over. On the morning of April 21, 1856, the bridge was completed, and the first trains rolled across it. Again, speeches were made and bands played. The Father of Waters had been crossed. Then disaster struck.

This drawing shows the locations of the various Rock Island bridges over the years. (William Riebe, "The Government Bridge," The Rock Island Digest)

A Collision Brings the Bridge to Court

Just fifteen days after the celebration of the completion of the bridge, part of the bridge was wrecked and burned as a result of a steamboat collision. This incident set the stage for act two of the court battle that helped to settle the issue of whether railroads could cross navigable streams. This incident also brought into the public eye an Illinois attorney by the name of Abraham Lincoln.

The story goes like this. As darkness fell on the evening of May 6, the steamer Effie Afton moved slowly upriver toward the newly completed bridge. The vessel blew her whistle signaling that she was moving through the draw. The draw slowly opened and the steamboat moved through. Some two hundred feet after the Effie Afton cleared the draw, she heeled hard to the right. Her starboard engine stopped, the port power seemingly increased. She struck the span next to the opened draw. The impact caused a great deal of damage to both the bridge and the boat. Then a stove in one of the cabins was knocked over and its fire spread rapidly to the deck and then to the bridge timbers. The vessel burned to cinders within five minutes. One span was completely destroyed, and there was some pier damage as well as minor damage to the rest of the bridge. By the following day, the rest of the bridge caught fire and was completely destroyed. Steamboats up and down the river celebrated, blowing whistles and ringing bells.

{snip}