Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

General Discussion

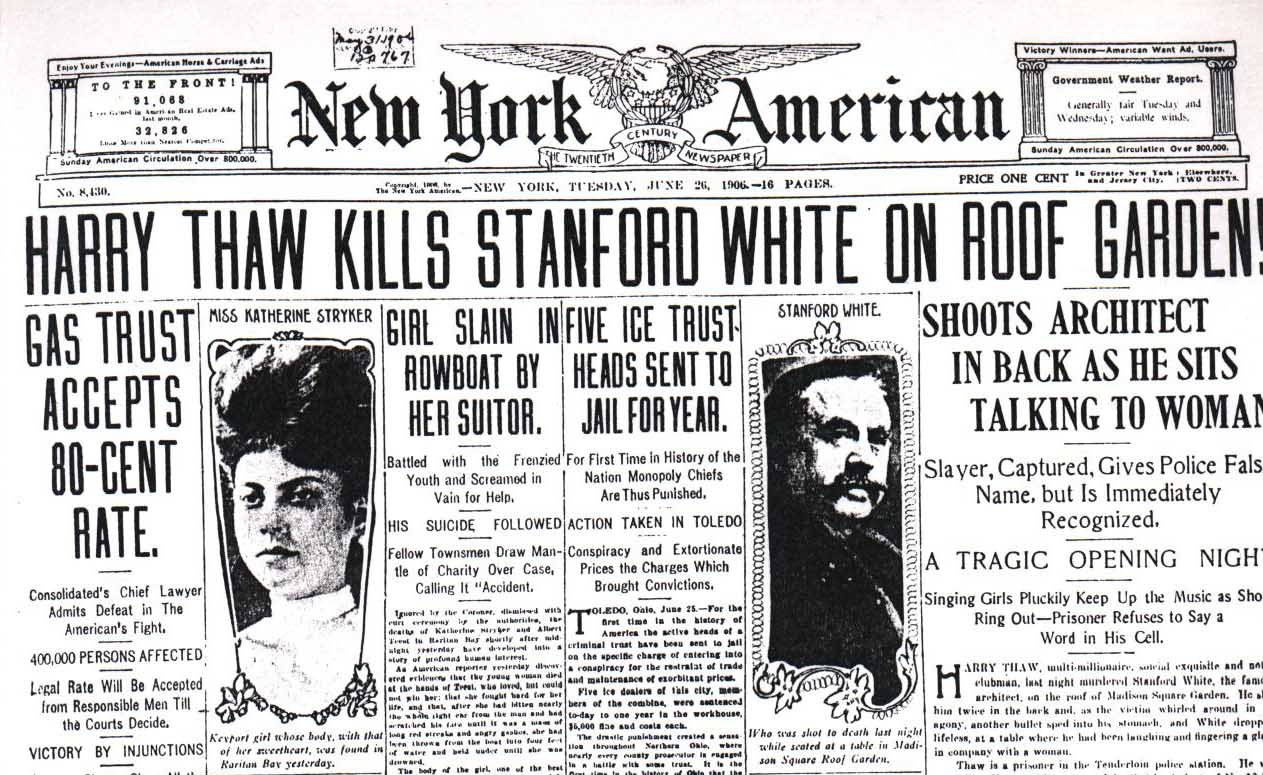

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region Forums113 Years Ago Today; Murder of the Century on the roof of Madison Square Garden

Stanford White, Evelyn Nesbit and Harry K Thaw.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanford_White

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect. He was also a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, the frontrunner among Beaux-Arts firms. He designed many houses for the rich as well as numerous public, institutional, and religious buildings. His design principles embodied the "American Renaissance".

The principals of the McKim, Mead & White architecture firm: William Rutherford Mead, Charles Follen McKim, and Stanford White (left to right)

In 1906, White was shot and killed by the mentally unstable millionaire Harry Kendall Thaw, who had become obsessed about White's previous relationship with Thaw's wife, actress Evelyn Nesbit. This led to a court case which was dubbed "The Trial of the Century" by contemporary reporters.

<snip>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evelyn_Nesbit

Florence Evelyn Nesbit (December 25, 1884 or 1885 – January 17, 1967) was an American artists' model, chorus girl, and actress.

In the early part of the 20th century, Nesbit's figure and face appeared frequently in mass circulation newspapers and magazine advertisements, on souvenir items, and in calendars, making her a celebrity. Her career began in her early teens in Philadelphia and continued in New York, where she posed for a cadre of respected artists of the era, including James Carroll Beckwith, Frederick S. Church, and notably Charles Dana Gibson, who idealized her as a "Gibson Girl". She had the distinction of being an early fashion and artists' model in an era when both fashion photography (as an advertising medium) and the pin-up (as an art genre) were just beginning their ascendancy.

Nesbit received further worldwide attention when her husband, the mentally unstable multimillionaire Harry Kendall Thaw, shot and killed the prominent architect and New York socialite Stanford White in front of hundreds of witnesses at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden on the evening of June 25, 1906, leading to what the press would call the "Trial of the Century". During the trial, Nesbit testified that five years earlier, when she was a stage performer at the age of 15 or 16, she had attracted the attention of White, who first gained her and her mother's trust, then sexually assaulted her while she was unconscious, and then had a subsequent romantic and sexual relationship with her that continued for some period of time.

<snip>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Kendall_Thaw

Harry Kendall Thaw (February 12, 1871 – February 22, 1947) was the son of Pittsburgh coal and railroad baron William Thaw Sr. Heir to a multimillion-dollar mine and railroad fortune, Thaw had a history of severe mental instability and led a profligate life. He is most notable for shooting and killing the renowned architect Stanford White on June 25, 1906, on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden in front of hundreds of witnesses. Thaw had become obsessed with his hatred of White. He thought White had blocked his access to the social elite of New York, and White had also had a previous relationship with Thaw's wife, the model/chorus girl Evelyn Nesbit. White and Nesbit had a sexual relationship in 1901–1902, when she was 16–17 years old, and their relationship had allegedly begun with White plying Nesbit with alcohol (and possibly drugs) and assaulting her while she was unconscious. In Thaw's mind, the relationship had "ruined" her. Thaw's trial for murder was heavily publicized in the press, to the extent that it was called the "trial of the century". After one hung jury, he was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

Plagued by mental illness throughout his life that was evident even in his childhood, Thaw spent money lavishly to fund his obsessive partying, drug addiction, abusive behavior toward those around him, and gratification of his sexual appetites. The Thaw family wealth allowed them to buy the silence of some of those who threatened to make public the worst of Thaw's reckless behavior and licentious transgressions. However, he had several additional serious confrontations with the criminal justice system, one of which resulted in seven more years of incarceration in a mental institution.

<snip>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Kendall_Thaw#Obsession_with_Stanford_White

Obsession with Stanford White

After his expulsion from Harvard, Thaw's sphere of activity alternated between Pennsylvania and New York. In New York, Thaw was determined to place himself amongst those privileged to occupy the summit of social prominence and to take his rightful place as a bona fide member of its rarefied atmosphere. His application for membership in the city's elite men's clubs – the Metropolitan Club, the Century Club, the Knickerbocker Club, the Players' Club – were rejected. His membership of the Union League Club of New York was summarily revoked when he rode a horse up the steps into the club's entrance way, a "behavior unbefitting a gentleman." All these snubs, Thaw was convinced, were directly or indirectly due to the intervention of the city's social lion, lauded architect Stanford White, who would not countenance Thaw's entry into these exclusive clubs. Thaw's narcissism rebelled at such a state of affairs and ignited a virulent animosity towards White. This was the first identifiable incident in a long line of perceived indignities heaped on Thaw, who maintained the unshakable certainty that his victimization was all orchestrated by White.

A second incident furthered Thaw's paranoid obsession with White. A disgruntled showgirl whom Thaw had publicly insulted reaped revenge when she sabotaged a lavish party Thaw had planned by hijacking all the female invitees and transplanting the festivities to White's infamous Tower room. Thaw, stubbornly ignorant of the real cause of the train of events, once again blamed White for single-handedly destroying his revelries. Thaw's social humiliation was completed when the episode was reported in the gossip columns. Thaw left with a stag group of guests, and a glaring absence of "doe-eyed girlies."

The reality was that Thaw both admired and resented White's social stature. More significantly, he recognized that he and White shared a passion for similar life styles. White, unlike Thaw, could carry on without censure, and seemingly with impunity.

Drug use

Various sources document Thaw's drug use, which became habitual after his expulsion from Harvard. He reportedly injected large amounts of cocaine and morphine, occasionally mixing the two drugs into one injection known as a speedball. He was known to also use laudanum; on at least one occasion he drank a full bottle in a single swallow. Thaw's drug addiction was verified when Evelyn Nesbit, Thaw's wife, found confirmation upon opening a bureau drawer. In her own words she related, "One day...I found a little silver box oblong in shape, about two and one half inches in length, containing a hypodermic syringe...I asked Thaw what it was for, and he stated to me that he had been ill, and had to make some excuse. He said he had been compelled to take cocaine."

Evelyn Nesbit

Relationship

Thaw had been in the audience of The Wild Rose, a show in which Evelyn Nesbit, a popular artist's model and chorus girl, was a featured player. The smitten Thaw attended some 40 performances over the better part of a year. Through an intermediary, he ultimately arranged a meeting with Nesbit, introducing himself as "Mr. Munroe". Thaw maintained this subterfuge, with the help of confederates, while showering Nesbit with gifts and money before he felt the time was right to reveal his true identity. The day came when he confronted Nesbit and announced with self-important brio, "I am not Munroe...I am Henry Kendall Thaw, of Pittsburgh!"

Candid about his dislike of Thaw, Stanford White warned Nesbit to stay away from Thaw. However, his cautions were generalizations, lacking the sordid specifics that would have alerted Nesbit to Thaw's all too real, aberrant proclivities. A bout of presumed appendicitis put Nesbit in the hospital and provided Thaw with an opportunity to insert himself emphatically into her life. Thaw came in bearing gifts and praise, managing to impress both Nesbit's mother and the headmistress at the boarding school Nesbit attended. Later, under Stanford White's orders, Nesbit was moved to a sanatorium in upstate New York, where both White and Thaw visited often, though never at the same time.

Nesbit had undergone an emergency appendectomy, at which time the kind-hearted side of Thaw came into play. He solicitously promoted a European trip, convincing mother and daughter that such a pleasure excursion would hasten Nesbit's recovery from surgery. However, the trip proved to be anything but recuperative. Thaw's usual hectic mode of travel escalated into a non-stop itinerary, calculated to weaken Nesbit's emotional resilience, compound her physical frailty, and unnerve and exhaust Mrs. Nesbit. As tensions mounted, mother and daughter began to bicker and quarrel, leading to Mrs. Nesbit's insistence on returning to the United States. Having effectively alienated her from her mother, Thaw then took Nesbit to Paris, leaving Mrs. Nesbit in London.

In Paris, Thaw continued to press Nesbit to become his wife; she again refused. Aware of Thaw's obsession with female chastity, she could not in good conscience accept his marriage proposal without revealing to him the truth of her relationship with Stanford White. What transpired next, according to Nesbit, was a marathon session of inquisition, during which time Thaw managed to extract every detail of that night—how—when plied with champagne—Nesbit lay intoxicated, unconscious—and White "had his way with her". Throughout the grueling question and answer ordeal, Nesbit was tearful and hysterical; Thaw by turns was agitated and gratified by her responses. He further drove the wedge between mother and daughter, condemning Mrs. Nesbit as an unfit parent. Evelyn Nesbit blamed the outcome of events on her own willful defiance of her mother's cautionary advice and defended her mother as naïve and unwitting.

Thaw and Nesbit traveled through Europe. Thaw, as guide, chose a bizarre agenda, a tour of sites devoted to the cult of virgin martyrdom. In Domrémy, France, the birthplace of Joan of Arc, Thaw left a telling inscription in the visitor's book: "she would not have been a virgin if Stanford White had been around."

Thaw took Nesbit to a castle, the Schloss Katzenstein in the Austrian Tyrol, the foreboding, gothic structure sitting near a high mountaintop. Thaw segregated the three servants in residence—butler, cook and maid—in one end of the castle; himself and Nesbit in the opposite end. This was where Nesbit said she then became Thaw's prisoner. She said she was locked in her room by Thaw, whose persona took on a dimension she had never before seen. Manic and violent, he beat her with a whip and sexually assaulted her over a two-week period. After his reign of terror had been expended, he was apologetic, and incongruously, after what had just transpired, was in an upbeat mood.

Marriage

Thaw had pursued Nesbit obsessively for nearly four years, continuously pressing her for marriage. Craving financial stability in her life, and in doing so denying Thaw's tenuous grasp on reality, Nesbit finally consented to become Thaw's wife. They were wed on April 4, 1905. Thaw himself chose the wedding dress. Eschewing the traditional white gown, he dressed her in a black traveling suit decorated with brown trim.

The two took up residence in the Thaw family mansion, Lyndhurst, in Pittsburgh. In later years Nesbit took measure of life in the Thaw household. The Thaws were anything but intellectuals. Their value system was shallow and self-serving, "the plane of materialism which finds joy in the little things that do not matter—the appearance of ...[things]."

Envisioning a life of travel and entertaining, Nesbit was rudely awakened to a reality markedly different; a household ruled over by the sanctimonious propriety of "Mother Thaw". Thaw himself entered into his mother's sphere of influence, seemingly without protest, taking on the pose of pious son and husband. It was at this time that Thaw instituted a zealous campaign to expose Stanford White, corresponding with the reformer Anthony Comstock, an infamous crusader for moral probity and the expulsion of vice. Because of this activity, Thaw became convinced that he was being stalked by members of the notorious Monk Eastman Gang, hired by White to kill him. Thaw started to carry a gun. Nesbit later corroborated his mind-set: "[Thaw] imagined his life was in danger because of the work he was doing in connection with the vigilance societies and the exposures he had made to those societies of the happenings in White's flat."

The killing of Stanford White

The second Madison Square Garden

It is conjectured that Stanford White was unaware of Thaw's long-standing vendetta against him. White considered Thaw a poseur of little consequence, categorized him as a clown, and most tellingly, called him the "Pennsylvania pug"—a reference to Thaw's baby-faced features.

June 25, 1906, was an inordinately hot day. Thaw and Nesbit were stopping in New York briefly before boarding a luxury liner bound for a European holiday. Thaw had purchased tickets for himself, two of his male friends, and his wife for a new show, Mam'zelle Champagne, playing on the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. In spite of the suffocating heat, which did not abate as night fell, Thaw inappropriately wore over his tuxedo a long black overcoat, which he refused to take off throughout the entire evening.

At 11:00pm, as the stage show was coming to a close, Stanford White appeared, taking his place at the table that was customarily reserved for him. Thaw had been agitated all evening, and abruptly bounced back and forth from his own table throughout the performance. Spotting White's arrival, Thaw tentatively approached him several times, each time withdrawing in hesitation. During the finale, "I Could Love A Million Girls", Thaw produced a pistol, and standing some two feet from his target, fired three shots at Stanford White, killing him instantly. Part of White's blood-covered face was torn away and the rest of his features were unrecognizable, blackened by gunpowder. Thaw remained standing over White's fallen body, displaying the gun aloft in the air, resoundingly proclaiming, according to witness reports, "I did it because he ruined my wife! He had it coming to him. He took advantage of the girl and then abandoned her!" (The key witness allowed that he wasn't completely sure he heard Thaw correctly – that he might have said "he ruined my life" rather than "he ruined my wife".)

An artist’s drawing of Stanford White’s shooting by Harry K. Thaw on the Madison Square Garden roof.

The crowd initially suspected the shooting might be part of the show, as elaborate practical jokes were popular in high society at the time. Soon, however, it became apparent that Stanford White was dead. Thaw, still brandishing the gun high above his head, walked through the crowd and met Evelyn at the elevator. When she asked what he had done, Thaw purportedly replied, "It's all right, I probably saved your life."

New York American on June 26, 1906

Trial

Thaw was charged with first-degree murder and denied bail. A newspaper photo shows Thaw in The Tombs prison seated at a formal table setting, dining on a meal catered for him by Delmonico's restaurant. In the background is further evidence of the preferential treatment the Thaw influence and money provided the incarcerated man. Conspicuously absent is the standard issue jail cell cot; during his confinement Thaw slept in a brass bed. Exempted from wearing prisoner's garb, he was allowed to wear his own custom tailored clothes. The jail's doctor was induced to allow Thaw a daily ration of champagne and wine. In his jail cell, in the days following his arrest, it was reported that Thaw heard the heavenly voices of young girls calling to him, which he interpreted as a sign of divine approval. He was in a euphoric mood; Thaw was unshakable in his belief that the public would applaud the man who had rid the world of the menace of Stanford White.

Thaw in jail cell on "Murderers' Row", Tombs Prison

The "Trial of the Century"

As early as the morning following the shooting, news coverage became both chaotic and single-minded, and ground forward with unrelenting momentum. Any person, place or event, no matter how peripheral to the incident, was seized on by reporters and hyped as newsworthy copy. Facts were thin but sensationalist reportage was plentiful in this, the heyday of tabloid journalism. The hard-boiled male reporters of the yellow press were bolstered by a contingent of female counterparts, christened "Sob Sisters". Their stock-in-trade was the human-interest piece, heavy on sentimental tropes and melodrama, crafted to pull on the emotions and punch them up to fever pitch. The rampant interest in the White murder and its key players were used by both the defense and prosecution to feed malleable reporters any "scoops" that would give their respective sides an advantage in the public forum. Thaw's mother, as was her custom, primed her own publicity machine through monetary pay-offs. The district attorney's office took on the services of a Pittsburgh public relations firm, McChesney and Carson, backing a print smear campaign aimed at discrediting Thaw and his wife Evelyn. Pittsburgh newspapers displayed lurid headlines; a sample of which blared, "Woman Whose Beauty Spelled Death and Ruin."

Only one week after the murder, a nickelodeon film, Rooftop Murder, was released, rushed into production by Thomas Edison.

Defense strategy

The main issue in the case was the question of pre-meditation. The formidable District Attorney, William Travers Jerome, at the outset, preferred not to take the case to trial by having Thaw declared legally insane. This was to serve a two-fold purpose. The approach would save time and money, and of equal if not greater consideration, it would avoid the unfavorable publicity that would no doubt be generated from disclosures made during testimony on the witness stand—revelations that threatened to discredit many of high social standing. Thaw's first defense attorney, Lewis Delafield, concurred with the prosecutorial position, seeing that an insanity plea was the only way to avoid a death sentence for their client. Thaw dismissed Delafield, who he was convinced wanted to "railroad [him] to Matteawan as the half-crazy tool of a dissolute woman."

Thaw's mother, however, was adamant that her son not be stigmatized by clinical insanity. She pressed for the defense to follow a compromise strategy; one of temporary insanity, or what in that era was referred to as a "brainstorm". Acutely conscious of the insanity in her side of the family, and after years of protecting her son's hidden life, she feared her son's past would be dragged out into the open, ripe for public scrutiny. Protecting the Thaw family reputation had become nothing less than a vigilant crusade for Thaw's mother. She proceeded to hire a team of doctors, at a cost of half a million dollars, to substantiate that her son's act of murder constituted a single aberrant act.

Possibly concocted by the yellow press in concert with Thaw's attorneys, the temporary insanity defense, in Thaw's case, was dramatized as a uniquely American phenomenon. Branded "dementia Americana", this catch phrase encompassed the male prerogative to revenge any woman whose sacred chastity had been violated. In essence, murder motivated by such a circumstance was the act of a man justifiably unbalanced.

The two trials

Harry K Thaw surrounded by onlookers as he leaves trial

Harry Thaw was tried twice for the murder of Stanford White. Due to the unusual amount of publicity the case had received, it was ordered that the jury members be sequestered—the first time in the history of American jurisprudence that such a restriction was ordered. The trial proceedings began on January 23, 1907, and the jury went into deliberation on April 11. After forty-seven hours, the twelve jurors emerged deadlocked. Seven had voted guilty, and five deemed Henry Kendall Thaw not guilty. Thaw was outraged that the trial had not vindicated the murder, that the jurors had not recognized it as the act of a chivalrous man defending innocent womanhood. He went into fits of physical flailing and crying when he considered the very real possibility that he would be labeled a madman and imprisoned in an asylum.] The second trial took place from January 1908 through February 1, 1908.

At the second trial, Thaw pleaded temporary insanity. This legal strategy was developed by Thaw's new chief defense counsel, Martin W. Littleton, whom Thaw and his mother had retained for $25,000. Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity, and sentenced to incarceration for life at the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Fishkill, New York. His wealth allowed him to arrange accommodations for his comfort and be granted privileges not given to the general Matteawan population.

Nesbit had testified at both trials. It is conjectured that the Thaws promised her a comfortable financial future if she provided testimony at trial favorable to Thaw's case. It was a conditional agreement; if the outcome proved negative, she would receive nothing. The rumored amount of money the Thaws pledged for her cooperation ranged from $25,000 to $1,000,000. Nesbit was now well aware that any solicitude or kindness shown her by the Thaw enclave was predicated on her pivotal performance on the witness stand. She was to present a pitiful portrait of innocence betrayed by the lascivious Stanford White. Thaw was to be the white knight whose noble, courageous act had avenged his wife's ruin. Throughout the prolonged court proceedings, Nesbit had received financial support from the Thaws. These payments, made to her through the Thaw attorneys, had been inconsistent and far from generous. After the close of the second trial, the Thaws virtually abandoned Nesbit, cutting off all funds. However, in an interview Nesbit's grandson, Russell Thaw, gave to the Los Angeles Times in 2005, it was his belief that Nesbit received $25,000 from the Thaw family after the end of the second trial. Nesbit and Thaw divorced in 1915.

Legal maneuvers: Push for freedom

Immediately after his commitment to Matteawan, Thaw marshaled the forces of a legal team charged with the mission of having him declared sane. The legal process was protracted.

In July 1909, Thaw lawyers attempted to have their client released from Matteawan on a writ of habeas corpus. Two key witnesses for the state gave testimony at the hearing detrimental to the defense. Landlady Susan "Susie" Merrill recounted a chronology of Thaw's activities during the period of 1902 through 1905. Merrill had rented apartments at two separate locations to Thaw, who presented himself under an alias. Using a false name and representing himself as a theatrical agent, Thaw then proceeded to bring girls into the premises, where he physically abused and emotionally terrorized them. Newspaper reports speculated on an item brought into evidence by Merrill. The "jeweled whip" was insinuated into the proceedings, a graphic element suggesting the scenarios played out in Thaw's rooms. Money was paid to keep the women silent. A Thaw attorney, Clifford Hartridge, corroborated Merrill's story, identifying himself as the intermediary who handled the monetary payoffs, some $30,000, between Merrill, the various women and Thaw. On August 12, 1910, the court dismissed the petition and Thaw was returned to Matteawan. The presiding judge wrote: "... the petitioner would be dangerous to public safety and was afflicted with chronic delusion insanity."

Determined to escape confinement, in 1913 Thaw walked out of the asylum and was driven over the Canadian border to Sherbrooke, Quebec. It is believed Thaw's mother, who had years of practice extricating her son from dire situations, orchestrated and financed her son's escape from Matteawan. His attorney, William Lewis Shurtleff, fought extradition back to the United States. Among Thaw's defense attorneys was future Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent. Thaw was taken to Mt. Madison House in Gorham, New Hampshire for the summer and kept under the watch of Sheriff Holman Drew, but in December 1914, Thaw was extradited to New York where he was able to secure a trial to establish whether he should still be considered insane. On July 16, 1915, the jury determined Thaw to be no longer insane, and set him free.

Throughout the two murder trials, as well as after Thaw's escape from Matteawan, a contingent of the public, seduced by the resulting exaggeration of the press, had become defenders of what they deemed Thaw's justifiable murder of Stanford White. Letters were written in support of Thaw, lauding him as a defender of "American womanhood". Sheet music was published for a musical piece titled: "For My Wife and Home".

Soon after the court decision, The Sun, in July, 1915, weighed in with its own estimation of the justice system in the Thaw matter: "In all this nauseous business, we don't know which makes the gorge rise more, the pervert buying his way out, or the perverted idiots that hail him with huzzas."

After Thaw's escape from Matteawan, Evelyn Nesbit had expressed her own feelings about her husband's most recent imbroglio: "He hid behind my skirts through two trials and I won't stand for it again. I won't let lawyers throw any more mud at me."

Evelyn Nesbit, age 69.

</snip>

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

10 replies, 3215 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (18)

ReplyReply to this post

10 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

113 Years Ago Today; Murder of the Century on the roof of Madison Square Garden (Original Post)

Dennis Donovan

Jun 2019

OP

no_hypocrisy

(46,087 posts)1. Allegedly attributed to Evelyn Nesbit about the murder of Stanford White:

"Stanny was lucky, he died. I lived."

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0626336/

(Personal quote)

Raine

(30,540 posts)2. Very interesting

Thanks for posting this! ![]()

Sherman A1

(38,958 posts)3. Thanks for posting

Javaman

(62,521 posts)4. Evelyn Nesbit was one of the original Gibson Girls...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gibson_Girl

The Gibson Girl was the personification of the feminine ideal of physical attractiveness as portrayed by the pen-and-ink illustrations of artist Charles Dana Gibson during a 20-year period that spanned the late 19th and early 20th century in the United States and Canada.[1] The artist saw his creation as representing the composite of "thousands of American girls".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evelyn_Nesbit

Florence Evelyn Nesbit (December 25, 1884 or 1885 – January 17, 1967) was an American artists' model, chorus girl, and actress.

In the early part of the 20th century, Nesbit's figure and face appeared frequently in mass circulation newspapers and magazine advertisements, on souvenir items, and in calendars, making her a celebrity. Her career began in her early teens in Philadelphia and continued in New York, where she posed for a cadre of respected artists of the era, including James Carroll Beckwith, Frederick S. Church, and notably Charles Dana Gibson, who idealized her as a "Gibson Girl". She had the distinction of being an early fashion and artists' model in an era when both fashion photography (as an advertising medium) and the pin-up (as an art genre) were just beginning their ascendancy.

The Gibson Girl was the personification of the feminine ideal of physical attractiveness as portrayed by the pen-and-ink illustrations of artist Charles Dana Gibson during a 20-year period that spanned the late 19th and early 20th century in the United States and Canada.[1] The artist saw his creation as representing the composite of "thousands of American girls".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evelyn_Nesbit

Florence Evelyn Nesbit (December 25, 1884 or 1885 – January 17, 1967) was an American artists' model, chorus girl, and actress.

In the early part of the 20th century, Nesbit's figure and face appeared frequently in mass circulation newspapers and magazine advertisements, on souvenir items, and in calendars, making her a celebrity. Her career began in her early teens in Philadelphia and continued in New York, where she posed for a cadre of respected artists of the era, including James Carroll Beckwith, Frederick S. Church, and notably Charles Dana Gibson, who idealized her as a "Gibson Girl". She had the distinction of being an early fashion and artists' model in an era when both fashion photography (as an advertising medium) and the pin-up (as an art genre) were just beginning their ascendancy.

colsohlibgal

(5,275 posts)5. That Was Such A Big Story At The Time

I saw a Documentary about this on Cable a few years ago. Big Deal in that time period.

BKDem

(1,733 posts)6. Years later in prison, Harry K. Thaw was

shown a photo of Marjorie Merriweather Post's Palm Beach estate, Mar a Lago. He is said to have remarked, "Oh my god, I killed the wrong architect."

ariadne0614

(1,727 posts)7. I was waiting for a Trumpenstein connection,

. . .but didn’t expect this one.

Dennis Donovan

(18,770 posts)10. Well played!

Welcome to DU!

Blue_Tires

(55,445 posts)8. And folks thought OJ was the trial of the century...

mahatmakanejeeves

(57,425 posts)9. Thank you for this great thread. I hadn't even thought about this.

More about Stanford White:

Stanford White

Photograph of White by George Cox, ca. 1892

....

Old Cabell Hall in the University of Virginia

....

McKim, Mead and White

Commercial and civic projects

William Rutherford Mead, Charles Follen McKim and Stanford White

In 1889, White designed the triumphal arch at Washington Square, which, according to White's great-grandson, architect Samuel G. White, is the structure White should be best remembered for. White was the director of the Washington Centennial celebration and created a temporary triumphal arch which was so popular, money was raised to construct a permanent version.

Elsewhere in New York City, White designed the Villard Houses (1884), the second Madison Square Garden (1890; demolished in 1925), the Cable Building – the cable car power station at 611 Broadway – (1893), the baldechin (1888 to mid-1890s) and altars of Blessed Virgin and St. Joseph (both completed in 1905) at St. Paul the Apostle Church; the New York Herald Building (1894; demolished); the IRT Powerhouse on 11th Avenue and 58th Street; the First Bowery Savings Bank, at the intersection of the Bowery and Grand Street (1894); Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square; the Century Club; and Madison Square Presbyterian Church, as well as the Gould Memorial Library (1903), originally for New York University, now on the campus of Bronx Community College and the location of the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.

Outside of New York City, White designed the First Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore, Maryland (1887), now Lovely Lane United Methodist Church. He also designed the Cosmopolitan Building, a three-story Neo-classical Revival building topped by three small domes, in Irvington, New York, built in 1895 as the headquarters of Cosmopolitan Magazine. He also designed Cocke, Rouss, and Old Cabell halls at the University of Virginia, and rebuilt The Rotunda (University of Virginia) in 1898, three years after it had burned down (his re-creation was later reverted to Thomas Jefferson's original design for the United States Bicentennial in 1976). Additionally, he designed the Blair Mansion at 7711 Eastern Ave. in Silver Spring, Maryland (1880), now being used as a violin store. He was responsible for designing the Boston Public Library and the Boston Hotel Buckminster, both still standing today. In 1902, he designed the Benjamin Walworth Arnold House and Carriage House in Albany, New York, and he helped to develop Nikola Tesla's Wardenclyffe Tower, his last design.

Just as his Washington Square Arch still stands (in Washington Square Park), so do many of White's clubhouses, which were focal points of New York society: the Century, Colony, Harmonie, Lambs, Metropolitan, and Players clubs. His Shinnecock Hills Golf Clubhouse design is said to be the oldest golf clubhouse in America and is now an iconic golf landmark. However, his clubhouse for the Atlantic Yacht Club, built in 1894 overlooking Gravesend Bay, burned down in 1934. Sons of society families also resided in White's St. Anthony Hall Chapter House at Williams College, now occupied by college offices.

Residential properties

In the division of projects within the firm, the sociable and gregarious White landed the majority of commissions for private houses. His fluent draftsmanship was highly convincing to clients who might not get much visceral understanding from a floorplan, and his intuition and facility caught the mood. White's Long Island houses have survived well, despite the loss of Harbor Hill in 1947, originally set on 688 acres (2.78 km2) in Roslyn. White's Long Island houses are of three types, depending on their locations: Gold Coast chateaux; neo-Colonial structures, especially those in the neighborhood of his own house at "Box Hill" in Smithtown, New York (White's wife was a Smith); and the South Fork houses from Southampton to Montauk Point. He also designed the Kate Annette Wetherill Estate in 1895.

....

Photograph of White by George Cox, ca. 1892

....

Old Cabell Hall in the University of Virginia

....

McKim, Mead and White

Commercial and civic projects

William Rutherford Mead, Charles Follen McKim and Stanford White

In 1889, White designed the triumphal arch at Washington Square, which, according to White's great-grandson, architect Samuel G. White, is the structure White should be best remembered for. White was the director of the Washington Centennial celebration and created a temporary triumphal arch which was so popular, money was raised to construct a permanent version.

Elsewhere in New York City, White designed the Villard Houses (1884), the second Madison Square Garden (1890; demolished in 1925), the Cable Building – the cable car power station at 611 Broadway – (1893), the baldechin (1888 to mid-1890s) and altars of Blessed Virgin and St. Joseph (both completed in 1905) at St. Paul the Apostle Church; the New York Herald Building (1894; demolished); the IRT Powerhouse on 11th Avenue and 58th Street; the First Bowery Savings Bank, at the intersection of the Bowery and Grand Street (1894); Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square; the Century Club; and Madison Square Presbyterian Church, as well as the Gould Memorial Library (1903), originally for New York University, now on the campus of Bronx Community College and the location of the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.

Outside of New York City, White designed the First Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore, Maryland (1887), now Lovely Lane United Methodist Church. He also designed the Cosmopolitan Building, a three-story Neo-classical Revival building topped by three small domes, in Irvington, New York, built in 1895 as the headquarters of Cosmopolitan Magazine. He also designed Cocke, Rouss, and Old Cabell halls at the University of Virginia, and rebuilt The Rotunda (University of Virginia) in 1898, three years after it had burned down (his re-creation was later reverted to Thomas Jefferson's original design for the United States Bicentennial in 1976). Additionally, he designed the Blair Mansion at 7711 Eastern Ave. in Silver Spring, Maryland (1880), now being used as a violin store. He was responsible for designing the Boston Public Library and the Boston Hotel Buckminster, both still standing today. In 1902, he designed the Benjamin Walworth Arnold House and Carriage House in Albany, New York, and he helped to develop Nikola Tesla's Wardenclyffe Tower, his last design.

Just as his Washington Square Arch still stands (in Washington Square Park), so do many of White's clubhouses, which were focal points of New York society: the Century, Colony, Harmonie, Lambs, Metropolitan, and Players clubs. His Shinnecock Hills Golf Clubhouse design is said to be the oldest golf clubhouse in America and is now an iconic golf landmark. However, his clubhouse for the Atlantic Yacht Club, built in 1894 overlooking Gravesend Bay, burned down in 1934. Sons of society families also resided in White's St. Anthony Hall Chapter House at Williams College, now occupied by college offices.

Residential properties

In the division of projects within the firm, the sociable and gregarious White landed the majority of commissions for private houses. His fluent draftsmanship was highly convincing to clients who might not get much visceral understanding from a floorplan, and his intuition and facility caught the mood. White's Long Island houses have survived well, despite the loss of Harbor Hill in 1947, originally set on 688 acres (2.78 km2) in Roslyn. White's Long Island houses are of three types, depending on their locations: Gold Coast chateaux; neo-Colonial structures, especially those in the neighborhood of his own house at "Box Hill" in Smithtown, New York (White's wife was a Smith); and the South Fork houses from Southampton to Montauk Point. He also designed the Kate Annette Wetherill Estate in 1895.

....

The Rotunda (University of Virginia)

....

Alterations

The Great Rotunda Fire in 1895

Renovation underway on the Rotunda in 2011, with the Jefferson statue in the foreground

The Dome Room of the Rotunda in 2008

A structure called the Annex, also known as "New Hall," was added to the north side of the Rotunda in 1853 to provide additional classroom space needed due to overcrowding. (A rare photograph of the Annex may be viewed at the University of Virginia's online visual history collection.)

In 1895, the Rotunda was entirely gutted by a disastrous fire that started in the Annex. University students saved what was, for them, the most important item within the Rotunda — a life-size likeness of Mr. Jefferson carved from marble that was given to the University by Alexander Galt in 1861; the students also rescued a portion of the books of the University library from the Dome Room, as well as various scientific instruments from the classrooms in the Annex. Shortly after the fire, the faculty drew up a recommendation to the Board of Visitors, recommending a program of rebuilding that called for the reconstruction of the Rotunda and the replacement of the lost classroom space of the Annex with a set of buildings at the south end of the Lawn. In the new design, the wooden dome was replaced with a fireproof tile dome by the Guastavino Company of New York in 1898-1899. The Rotunda was rebuilt with a modified design by Stanford White, a nationally known architect and partner in the New York City firm McKim, Mead, and White . Whereas Jefferson's Rotunda had three floors, White's had only two, but a larger Dome Room. In addition, the Annex was not rebuilt.

In 1976 during America's Bicentennial, White's Rotunda interior was gutted and completely rebuilt, at a cost of $2.4 million, to Jefferson's original design. In the Bicentennial issue of the AIA Journal, the American Institute of Architects called Jefferson's Rotunda, Lawn, and nearby home at Monticello "the proudest achievement of American architecture in the past 200 years".

There is a plaque, on the south side of the Rotunda, listing the names of students and graduates of The University who were killed during the Civil War. Other plaques on the south side list those killed during World War I while plaques on the north side list those killed in World War II and the Korean War.

Today, doctoral students defend their dissertations in the North Oval Room, and many events (including monthly dinners for residents of the Lawn) are held inside the Dome Room. Other important events are held on the steps of the Rotunda, which is also the traditional starting point for students streaking the Lawn.

In 2012, the University began an extensive construction project to repair and renovate the aging Rotunda. The first phase of the project will replace the Rotunda's copper roof. Although the engineers were several months ahead of schedule, the roof remained an unpainted copper for the graduating class of 2013. During the renovation, a nineteenth-century chemistry laboratory was found within the walls on the bottom floor featuring a chemical hearth and a sophisticated ventilation system through a series of brick tunnels. The Newly renovated Rotunda opened in September 2016.

....

Alterations

The Great Rotunda Fire in 1895

Renovation underway on the Rotunda in 2011, with the Jefferson statue in the foreground

The Dome Room of the Rotunda in 2008

A structure called the Annex, also known as "New Hall," was added to the north side of the Rotunda in 1853 to provide additional classroom space needed due to overcrowding. (A rare photograph of the Annex may be viewed at the University of Virginia's online visual history collection.)

In 1895, the Rotunda was entirely gutted by a disastrous fire that started in the Annex. University students saved what was, for them, the most important item within the Rotunda — a life-size likeness of Mr. Jefferson carved from marble that was given to the University by Alexander Galt in 1861; the students also rescued a portion of the books of the University library from the Dome Room, as well as various scientific instruments from the classrooms in the Annex. Shortly after the fire, the faculty drew up a recommendation to the Board of Visitors, recommending a program of rebuilding that called for the reconstruction of the Rotunda and the replacement of the lost classroom space of the Annex with a set of buildings at the south end of the Lawn. In the new design, the wooden dome was replaced with a fireproof tile dome by the Guastavino Company of New York in 1898-1899. The Rotunda was rebuilt with a modified design by Stanford White, a nationally known architect and partner in the New York City firm McKim, Mead, and White . Whereas Jefferson's Rotunda had three floors, White's had only two, but a larger Dome Room. In addition, the Annex was not rebuilt.

In 1976 during America's Bicentennial, White's Rotunda interior was gutted and completely rebuilt, at a cost of $2.4 million, to Jefferson's original design. In the Bicentennial issue of the AIA Journal, the American Institute of Architects called Jefferson's Rotunda, Lawn, and nearby home at Monticello "the proudest achievement of American architecture in the past 200 years".

There is a plaque, on the south side of the Rotunda, listing the names of students and graduates of The University who were killed during the Civil War. Other plaques on the south side list those killed during World War I while plaques on the north side list those killed in World War II and the Korean War.

Today, doctoral students defend their dissertations in the North Oval Room, and many events (including monthly dinners for residents of the Lawn) are held inside the Dome Room. Other important events are held on the steps of the Rotunda, which is also the traditional starting point for students streaking the Lawn.

In 2012, the University began an extensive construction project to repair and renovate the aging Rotunda. The first phase of the project will replace the Rotunda's copper roof. Although the engineers were several months ahead of schedule, the roof remained an unpainted copper for the graduating class of 2013. During the renovation, a nineteenth-century chemistry laboratory was found within the walls on the bottom floor featuring a chemical hearth and a sophisticated ventilation system through a series of brick tunnels. The Newly renovated Rotunda opened in September 2016.